The Fur Post at Ginebig-ziibi (Snake River)

The land on which the Snake River Fur Post was constructed in 1804 was, and still is, Ojibwe homeland. When the post was built, the Ojibwe had already held a powerful position in the fur trade for over 175 years. Their homeland and influence reached from the Great Lakes, west to the Great Plains, and north to the homelands of the Cree and Assiniboine. With the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, the United States laid colonial claim to much of present-day Minnesota. However, the United States had no real presence in the region and the Indigenous peoples of the area continued to trade with British companies.

Incorporated in 1779 and headquartered in Montreal, the North West Company established commercial operations extending west to the Rocky Mountains. The company traded with the Ojibwe living in present-day Canada, Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota. Eager to expand its business, and compete with the XY Company, the North West Company sent experienced trader John Sayer to the lands of the Snake River band of Ojibwe in 1804.

The Ojibwe had a centuries-long history of leveraging their political and economic power to influence when and where trading posts were established. They played the XY and North West companies against one another, prompting the North West Company to send additional traders into their lands. A North West company employee named Joseph Reaume had been trading on the Snake River since 1802 and Sayer had visited the region previously. But in 1804, Sayer was ordered to establish a more permanent band-level post to satisfy the Ojibwe living near the Ginebig-ziibi (Snake River). This area was within what the North West Company called the Folle Avoine (Wild Rice) Department of the Fond du Lac District.

Sayer had been working for British fur trade companies since the 1770s in the Fond du Lac District, southwest of Lake Superior. He was a bourgeois, a French term denoting his status as a wintering partner and stockholder with the North West Company. Bourgeois were the highest ranking employees to work directly with Native Americans. Sayer spent considerable time at Grand Portage and Fond du Lac. The Ojibwe incorporated Sayer into their kinship and cultural practices. They taught Sayer their language and the Indigenous custom of reciprocity which governed the fur trade.

An Ojibwe woman named Obemau-unoqua, daughter of a leader named Mamongazida, married Sayer and they started a family. Obemau-unoqua came from an influential Ojibwe family who lived at Chequamegon in present-day Wisconsin. Her father was a renowned hunter and war leader. After his death, her brother, Waubojeeg, rose to prominence as a leader. Obemau-unoqua also had kinship ties to the Bdewakantunwan Dakota. As the wife of a bourgeois, Obemau-unoqua held a privileged status and servants attended to her needs. She also took the English name Nancy Sayer. Marriages between Native American women and traders helped create the kinship, political, and economic ties that formed the basis of fur trade culture.

When Sayer and his party arrived in the area they were welcomed by the local Ojibwe. Gifts were exchanged, and the Ojibwe recommended Sayer’s party build a post on the banks of Ginebig-ziibi. The trading party constructed the Snake River Fur Post from October 9 to November 20, 1804. The post included a rowhouse with six rooms that included living quarters, a storehouse, and a room where trade was conducted. The rowhouse was enclosed by a stockade with a single entrance.

Through the winter of 1804–1805 the local Ojibwe trapped beaver and hunted other fur-bearing animals. Sayer’s employees spent much of their time hunting, chopping firewood, and visiting the winter lodges of the Ojibwe. Ojibwe people from communities on the Yellow, St. Croix, and Snake rivers, as well as Lake Pokegama, interacted with Sayer’s company. They represented their people’s interests and worked as hunters, trappers, and guides. Some known names of the local Ojibwe were Miqauanance, Kisketawak, Wishaima, and Shagobay. With the onset of spring the Ojibwe brought their furs to Sayer, traded for goods, and settled any debts. On April 26, 1805, the North West Company party left the Snake River Fur Post and returned to Fort St. Louis at Fond du Lac. It is unknown if the Snake River Fur Post was used after Sayer’s party departed in 1805. Eventually the buildings fell into ruin and burned.

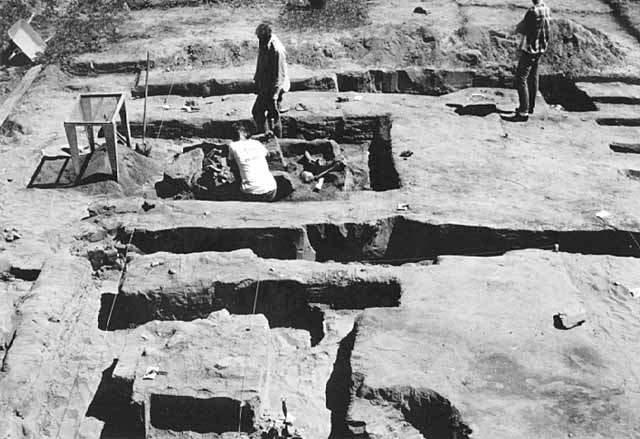

In 1963, the Minnesota Historical Society conducted field testing at the site on the advice of a local who believed the area to be the former location of the Snake River Fur Post. The tests were positive and archaeology continued over the next three summers. The Minnesota Historical Society purchased the land and in 1966 the Minnesota Legislature funded the reconstruction of the post. The historic site opened to the public in 1970. In 2018, the Minnesota Historical Society renamed the site the Snake River Fur Post in order to reflect historical precedent and better represent the diverse stories told at the site.

Resources

- Backerud, Thomas K. “Fort St. Louis/Fond du Lac, Lake Superior.” MNopedia, March 4, 2013.

- Bedworth, Jacalyn. “Sayer, John (1750–1818).” MNopedia, December 12, 2016.

- Birk, Douglas. “Sayer, John.” Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. 5. Toronto, CA: University of Toronto, 2003.

- —. The Messrs. Build Commodiously: A Guide to John Sayer’s 1804–1805 North West Company Wintering Expedition to the Snake River, Minnesota. [Brainerd, MN]: Evergreen Press of Brainard, 2004.

- — and Bruce M. White. “Who Wrote the ‘Diary of Thomas Connor?” Minnesota History 46, no. 5 (Spring 1979): 170–188.

- Brown, Jennifer S. H. Strangers in Blood: Fur Trade Company Families in Indian Country. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1980.

- Buffalohead, Priscilla. “Farmers, Warriors, Traders: A Fresh Look at Ojibway Women.” Minnesota History 48. No. 6 (Summer 1983): 236–244.

- Campbell, Marjorie Wilkins. The Northwest Company. Vancouver, CA: Douglas & McIntyre, 1983. Third Edition.

- Coddington, Donn M. “A Fur Trade Mystery Solved.” Early Man 4, no. 2 (Spring 1982); 16–20.

- Gilman, Carolyn. Where Two Worlds Meet: The Great Lakes Fur Trade. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1982.

- Goodsky, Sandra L. Angwaamas: It’s About Time; A Research Report on the Ojibwe-European Fur Trade Relations from an Ojibwe Perspective. Duluth, MN: Blue Sky Consulting [1993].

- Morrison, David A. “The North West Company, 1779–1821.” The Canadian Encyclopedia, October 18, 2013.

- Nelson, George. My First Years in the Fur Trade: The Journals of 1802–1804. Edited by Laura Peers and Theresa Schenck. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2002.

- Nute, Grace Lee. The Voyageur. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1987.

- Podruchny, Carolyn. Making the Voyageur World: Travelers and Traders in the North American Fur Trade. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2006.

- Podruchny, Carolyn and Laura Peers, eds. Gathering Places: Aboriginal and Fur Trade Histories. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2010.

- Ray, Arthur J. Indians in the Fur Trade: Their Role as Trappers, Hunters, and Middlemen in the Lands Southwest of Hudson Bay, 1660–1870. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1974.

- Sayer, John. John Sayer’s Snake River Journal, 1804–1805: A Fur Trade Diary From East Central Minnesota. Edited by Douglas Birk. [Minneapolis, MN: Institute for Minnesota Archaeology, 1989].

- Van Kirk, Sylvia. “Many Tender Ties”: Women in Fur-trade Society in Western Canada, 1670-1870. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1983.

- Warren, William. History of the Ojibwe People. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1984.

- White, Bruce. “A Skilled Game of Exchange: Ojibway Fur Trade Protocol.” Minnesota History 50, no. 6 (Summer 1987): 228–240.

- Wingerd, Mary Lethert. North Country: The Making of Minnesota. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010.

North West Company coat of arms, about 1800–1820. Source: Library and Archives Canada.

Archaeological work at the Snake River Fur Post, 1964. Source: Source: MNHS Collections.