Construction of the Lighthouse

Split Rock was one of the most remote and dangerous locations on the Great Lakes, requiring great feats of strength and ingenuity to erect a lighthouse.

Ralph Russell Tinkham

While a junior engineer of the U.S. Lighthouse Establishment, Ralph Russell Tinkham sailed up the North Shore as an assistant on the Rock of Ages Light project near Isle Royale. His ship passed an isolated cliff of anorthrosite rock, poised like a sentinel above the waters of Lake Superior.

He didn't know it at the time, but that cliff would later consume almost a year and a half of his life and catapult his career with the U.S. Lighthouse Service. It would be the site of the Split Rock Light Station.

Tinkham enjoyed the challenge of building lighthouses in remote, inaccessible areas. During the construction, he did all the architectural work, determined material and labor needs, and watched over the construction on-site, living in the upstairs of the first storage barn after its completion early in 1909.

By the time of his retirement in 1946, Tinkham had become the chief engineer of the entire U.S. Lighthouse Service, and had planned and watched over the construction of stations in a number of harsh and unforgiving locations, including Hawaii and Alaska.

A marvel of engineering

The construction of Split Rock Lighthouse was an engineering feat for an organization already known for building structures in remote locations.

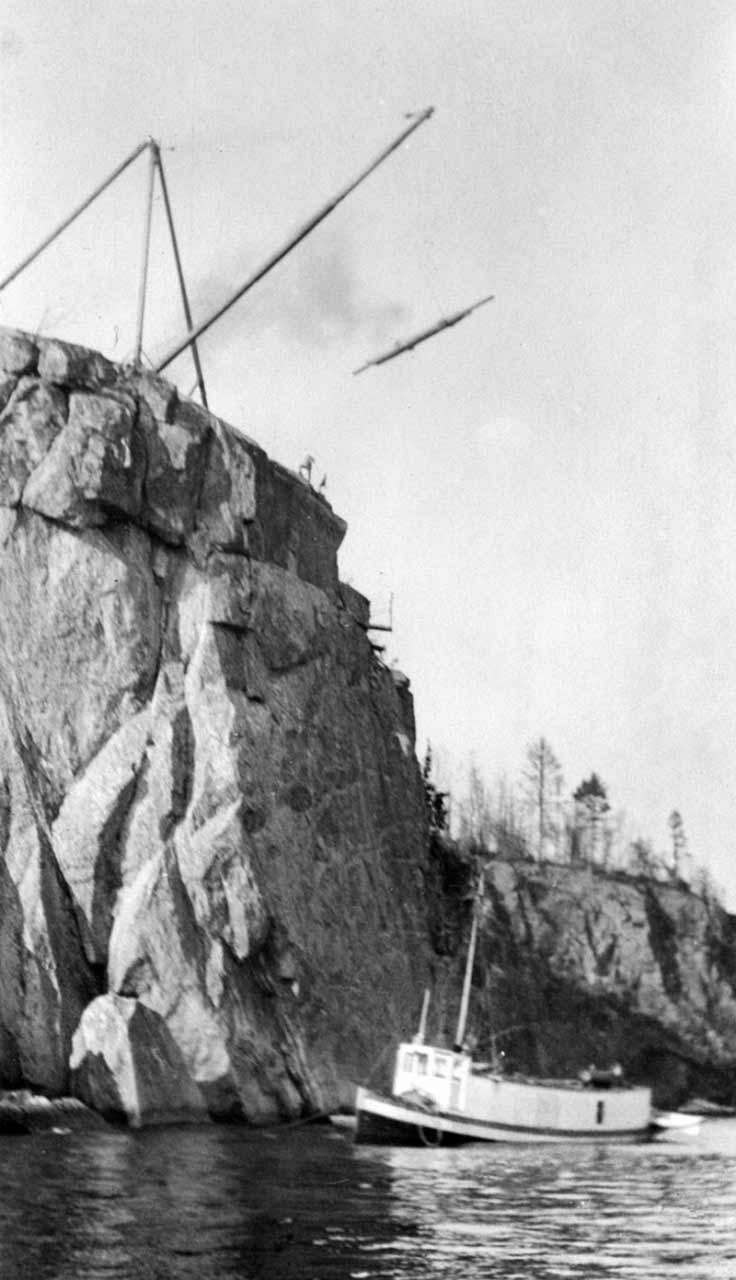

The spring of 1909 welcomed the first challenge: erecting a steam-powered hoist and derrick on the rocky cliffside for lifting supplies off the supply boats on the lake, more than 110 feet below. Because there were no roads, boats would supply the construction crew of 35 to 50 men throughout construction. In the end, 310 tons of building materials were hoisted to the site without a single major accident.

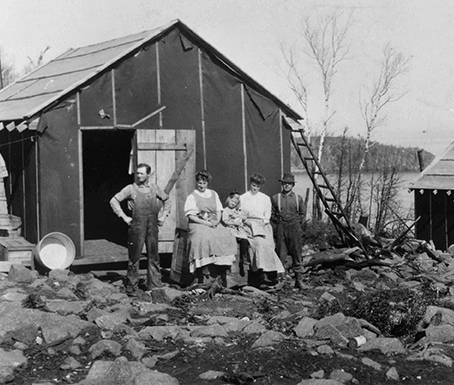

The construction workers stayed in canvas tents on the open cliff top as construction proceeded. Duluth construction firm L.D. Campbell & Son supplied all the labor necessary to assemble the station at one of the most remote places one had ever been built. Carpenters, brick masons, demolition men for dynamiting the hard rock of the cliff for foundations, and common laborers collected from all over the Great Lakes region came together for the project.

By the time Split Rock Light Station was completed in mid-summer 1910, workers had spent 13 months on the desolate cliff, with only a break during the worst months of winter. They were exposed to the elements and connected to civilization only by occasional supply boat visits. When the light was first lit on July 31, 1910, it stood as a monument to the will of the men who built it as much as an aid to navigation.